The Human Toll

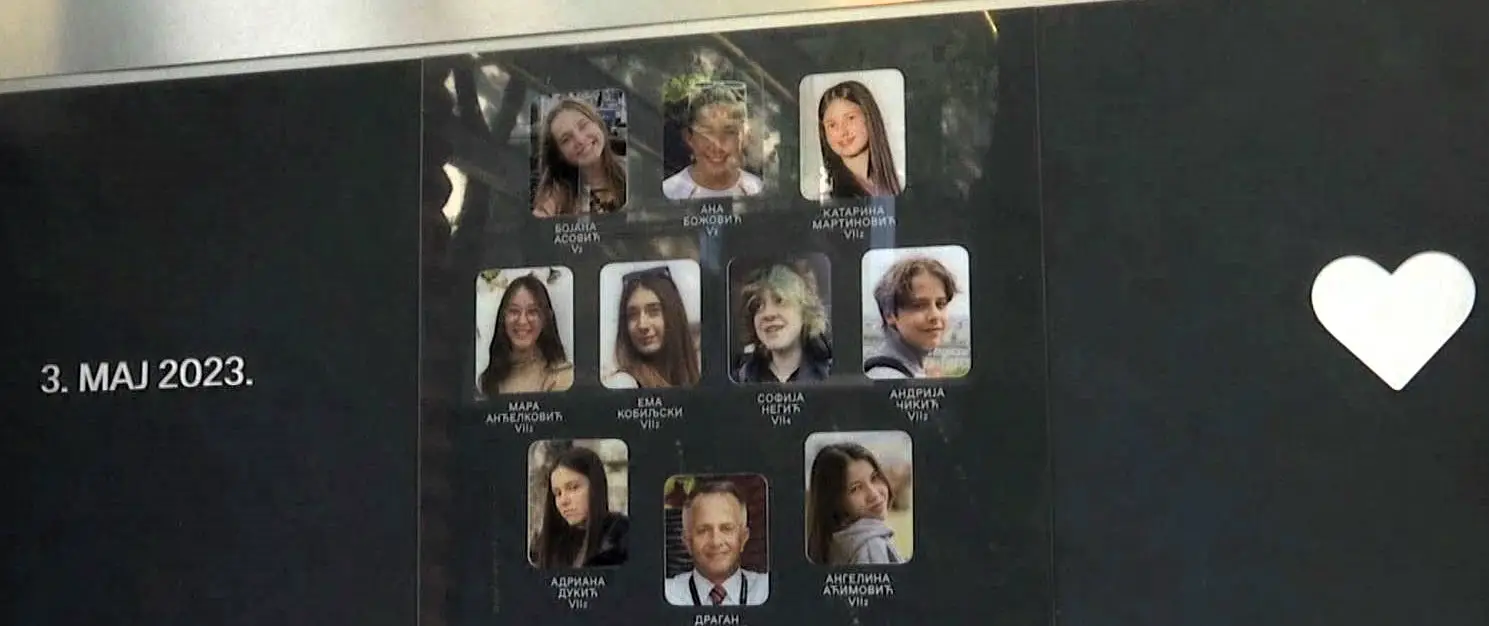

In Montenegro, a grandmother mourns her grandsons Mašan and Marko, killed in Cetinje’s mass shooting in 2022. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the faces of 19-year-old Faris Pendek and 52-year-old Amra Kahrimanović, both killed in 2024, have become symbols of calls for reform. In Croatia’s Daruvar, the massacre of six nursing home residents left survivors living with nightly terror. In Serbia, a series of tragedies – from domestic murders to the school mass shooting in Belgrade in 2023 – has underscored the scale of the problem.

Photo: RTCG

“I never imagined that Marko and Mašan would never come back. And my daughter too.”

Vesna Pejović, grandmother of Cetinje victims, Montenegro

Photo: HRT

“I can’t sleep because I dream about that incident, I wake up with those images, and whenever evening falls, I feel like somebody is taking aim at me.”

Ana Ivandekić, owner of the Home for the Elderly and Disabled in Daruvar, Croatia

- The Ribnikar elementary school mass shooting victims on the Angelina foundation wall, Belgrade, Serbia Photo: RTS

These tragedies share a common thread: easy access to guns – many illegal – and systems that fail to prevent violence before it starts.

The Numbers Behind the Violence

In police storage rooms from Sarajevo to Zagreb, thousands of surrendered rifles, pistols, and shotguns are stacked floor to ceiling. Yet for every weapon handed in, experts say many more remain hidden in homes, basements, and fields.

Ljubomirka Ljupka Kovačević, activist and psychologist, Montenegro

Video: RTCG

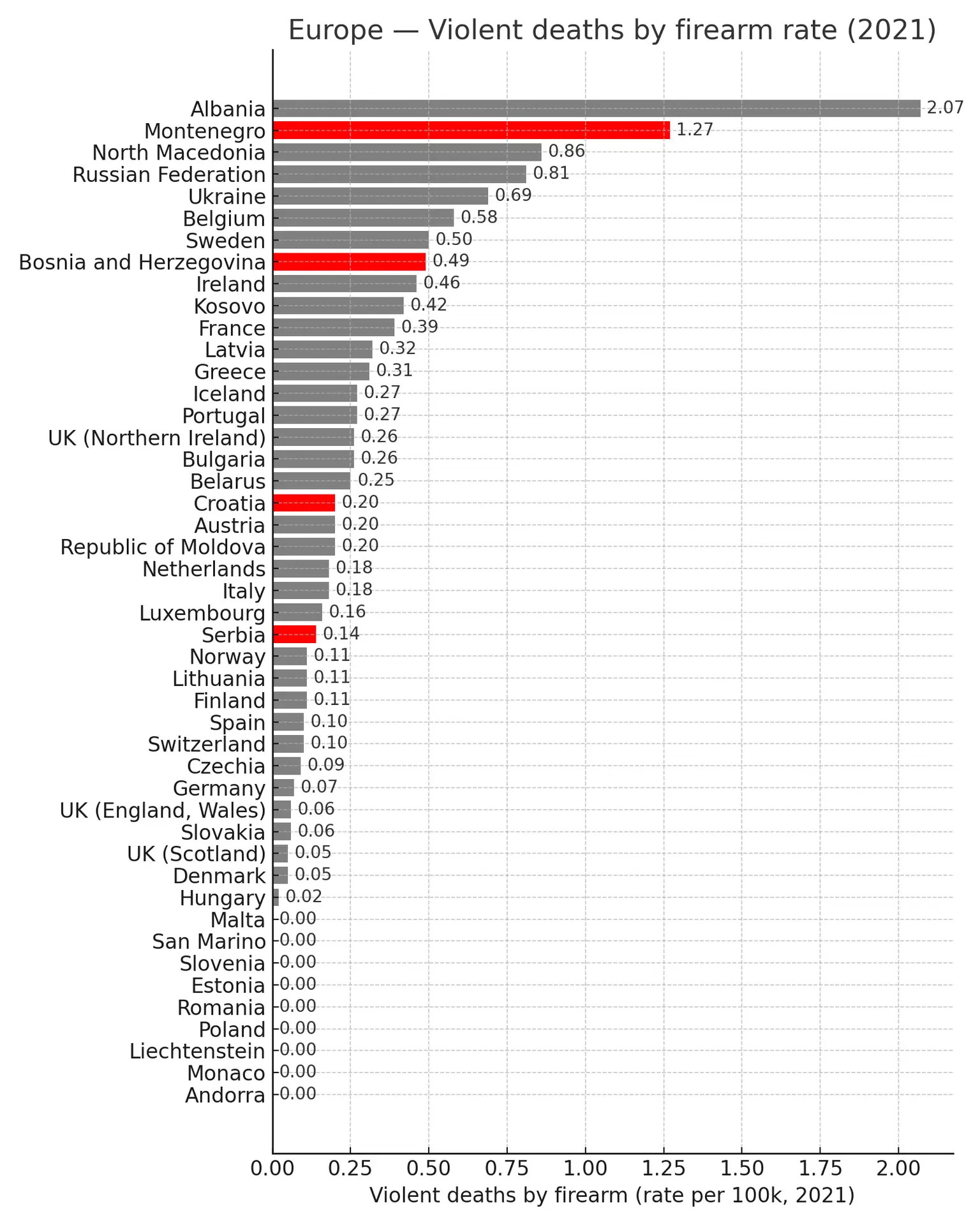

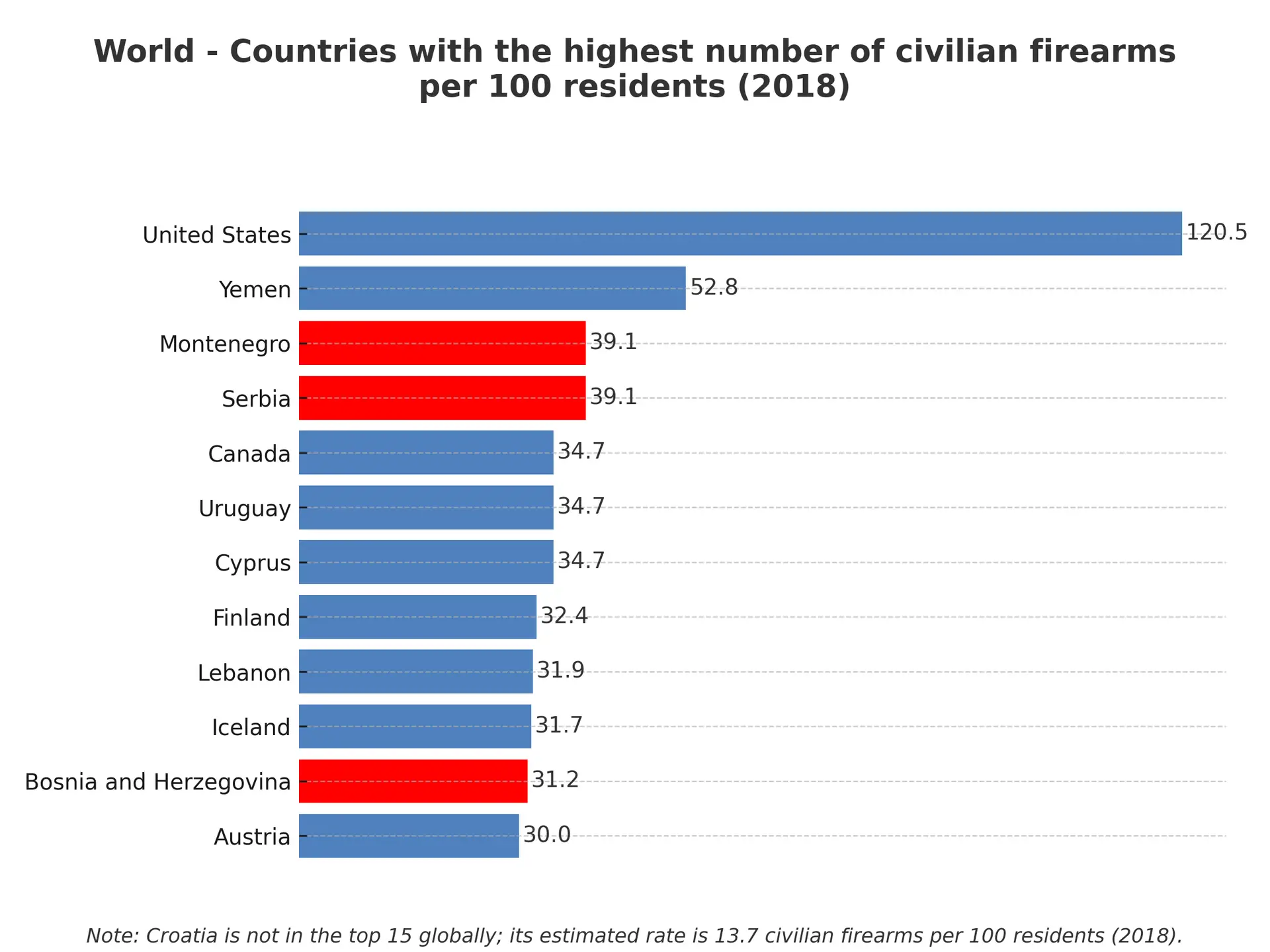

Regional data reveals a sobering picture: gun ownership per capita in some Balkan countries is among the highest in Europe, and the proportion of violent crimes involving illegal firearms is alarmingly high.

Data from SEESAC and national authorities shows that:

– In Serbia: Over half a million legal gun owners; 2,123 firearm incidents in 5 years; 58 domestic violence victims killed with guns.

-In Croatia: 9 out of 10 firearm murders committed with illegal weapons; 370,000 guns surrendered since 2007.

SOURCE: Small Arms Survey

SOURCE: Small Arms Survey

– In Montenegro: 108,000 registered firearms for just 633,000 people; 3,700 guns surrendered in 2025 alone.

– In Montenegro: 108,000 registered firearms for just 633,000 people; 3,700 guns surrendered in 2025 alone.

– In Bosnia and Herzegovina: 350,000 registered firearms, 850,000 illegal ones; 96% of crimes committed with illegal guns.

How Guns Become Part of Life

The roots of today’s gun problem run deep, tracing back to the wars of the 1990s, when homes across the region were turned into makeshift arsenals. Even earlier, in many communities, firearms were more than tools of survival – they were symbols of pride and tradition. In rural households, a rifle could be passed down like a family heirloom, a gesture of trust and respect.

Criminologist Aleksandar Stevanović in Belgrade describes it as “a culture of weapons” – a mindset where gun ownership is not just about protection, but about identity. In Montenegro, sociologist Vladimir Bakrač recalls a time when “receiving a gun meant you were an adult, worthy of responsibility.”

Aleksandar Stevanovic, a criminology researcher, Serbia

Video: RTS

But the meaning has shifted. What once represented maturity and honour now fuels a thriving illegal market. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, MP Nebojša Vukanović warns that without coordinated police action, “the illegal trade will keep thriving.”

Unnamed witness, Croatia

Video: HRT

Meanwhile, Croatian psychiatrist Katarina Dodig-Ćurković sees the cultural handover of firearms as a dangerous cycle: “These weapons are often the trigger for aggression,” she says, pointing to “a transgenerational transfer from parents to descendants and grandchildren.”

System Failures: Mental Health and Law Enforcement

In several of the region’s most harrowing tragedies, the perpetrators were active or former police officers – people entrusted with public safety who were themselves struggling with unaddressed trauma, stress, or psychological instability. Investigations have revealed alarming gaps in routine mental health assessments for law enforcement. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, MP Nebojša Vukanović points out that systematic psychological evaluations for police have not been carried out for a decade, leaving potentially unstable officers armed and on duty.

“We had a minister who fired a gun in a car, filmed it, filmed himself firing a gun that was illegal, and many didn’t even see a problem with it.

Dušan Miljuš, “Jutarnji list” reporter, Croatia

“Mass shootings are often linked to isolation, revenge motives – and access to firearms. The last is the easiest to fix.”

Prof. Dr. Milica Pejovic Milovancevic, Child Psychiatrist, Serbia

Experts warn that this is part of a wider pattern. Across the Balkans, overstretched mental health services, combined with stigma and a culture of silence, mean that warning signs often go unnoticed. In Serbia, psychiatrist Milica Pejović-Milovančević stresses that social isolation – particularly among young people – combined with the easy availability of firearms, creates a volatile mix that can lead to mass shootings.

Disarmament in Action

Across the region, authorities are stepping up campaigns to reduce the number of weapons in circulation. Serbia has extended its ban on new gun registrations until the end of 2025, seizing thousands of illegal firearms and encouraging voluntary surrender with no penalties. In Croatia, the long-running “Fewer Weapons, Fewer Tragedies” campaign has removed hundreds of thousands of weapons since 2007. Montenegro launched the “Respect Life, Return the Weapons” campaign, offering citizens the opportunity to hand over weapons with no legal consequences. Named in memory of Marko and Masan, the ‘Marko and Masan’s Law’ that should be adopted in autumn 2025, calls for weapons to be confiscated from violent offenders and for psychological assessments to be mandatory before issuing and renewing licenses. Bosnia and Herzegovina, with OSCE support, is working to harmonize firearm laws across its complex political structure to ensure consistent enforcement.

From Horror to Hope

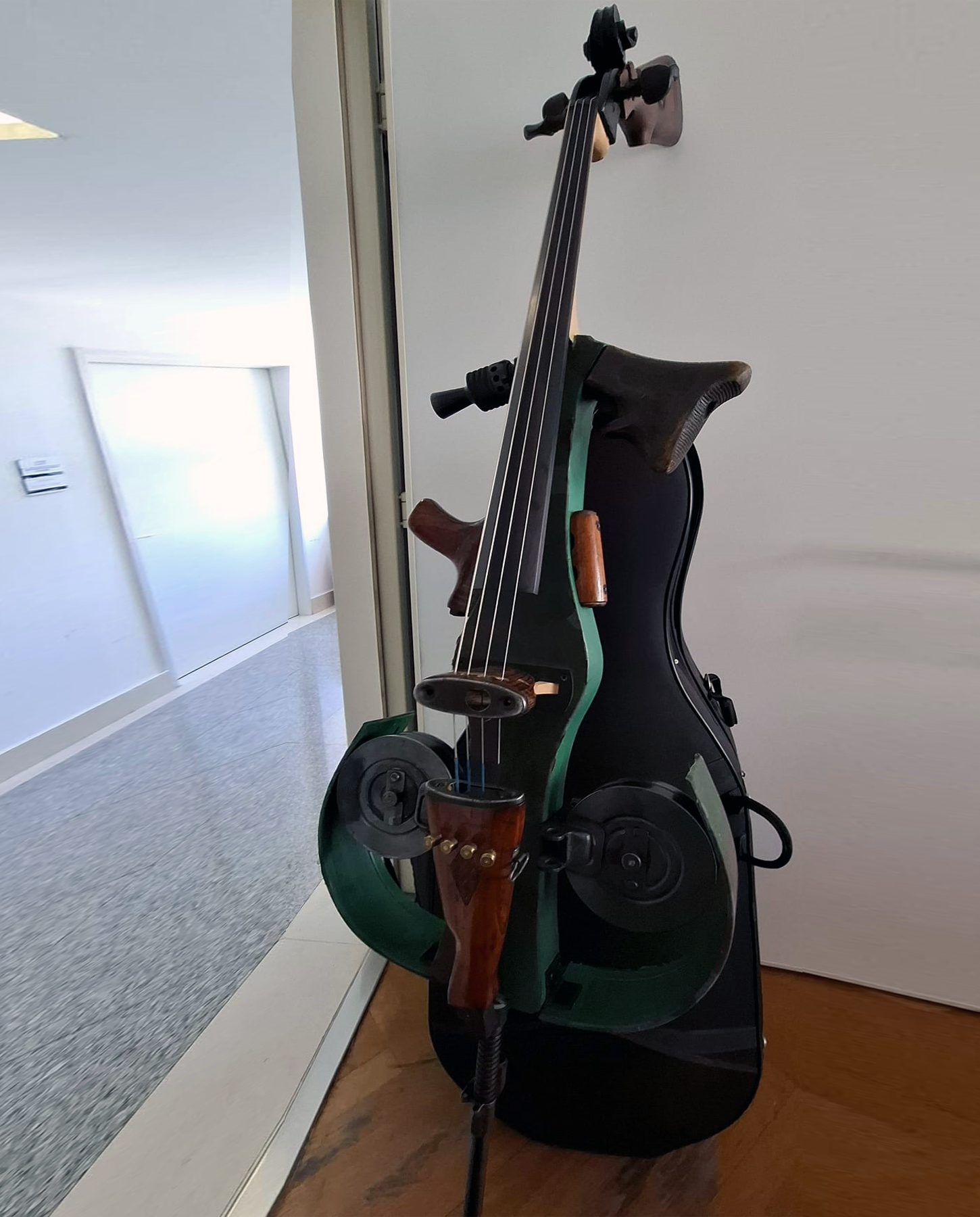

Amid the grief, some are transforming tragedy into action. In Croatia, music pedagogue Zoran Gojmerac turns surrendered weapons into cellos – replacing the sound of gunfire with music. In Serbia, the Angelina Foundation, created after the Ribnikar school shooting, works to protect children from online abuse and offline violence. Montenegro’s “School Without Violence” program teaches students to recognize and report abuse early. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, citizen protests are pushing for stricter gun laws and better mental health services for police.

Music pedagogue Zoran Gojmerac crafting a cello from surrendered firearms

Photo: HRT

A surrendered weapon transformed into music:

cello by Zoran Gojmerac

Photo: HRT

Cellist Ana Rucner playing the cello

made out of guns

Photo: HRT

Hotlines for voluntary surrender

Croatia – 192

Montenegro – 122

This article was produced by the ERNO Coordination Office, within SoJo Europe Programmes

For more information about ERNO and our activities, please contact:

📧 yle_sa@erno.ba | ☎ +387 33 461526

© 2025 ERNO – Eurovision News Exchange for Southeast Europe